April 05,2012

Posted by Made It Myself Books

April 04,2012

Posted by Haggadot

It’s not the only thing (thankfully!) that we eat at Passover, but there is no question that matzah is THE food of the holiday. Matzah, also known as “the bread of affliction,” is the big symbol at the Seder table. We hold it up in the air for acknowledgement and are required to eat a portion of it…we even hide a piece for the children to find.

There are all types of matzah too; egg matzah, whole wheat matzah, thin matzah, and of course, shmurah matzah. The latter is matzah that has been been hand-made and guarded from start to finish to ensure that it follows the most stringent laws of observance. Whether you spell it matzo or matzah, you can enjoy some of our favorite clips about it:

Never before seen DIY Matzoh Baking

A Moroccan Tradition of Passing the Matzah

If you want to take it a step further, you can always make your own matzah!

April 03,2012

Posted by Haggadot

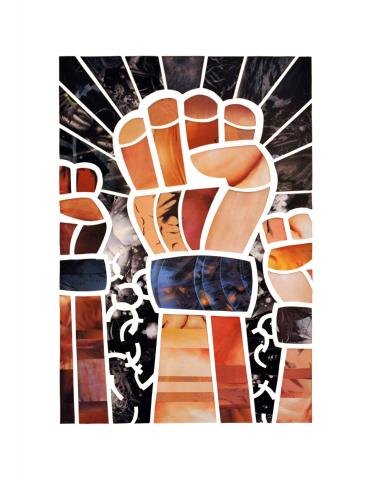

Adding visually engaging and interactive pieces to your Haggadah helps to promote thoughtful discussion at the Seder table. We are so fortunate to have such an amazing collection of work from so many talented artists on Haggadot.com.

Here are a few highlights from the Los Angeles creative community:

April 02,2012

Posted by Haggadot

If you are searching for some material to make your Haggadah more child/teen friendly, here is a supplement with some great clips from different Haggadot.com contributors. This is a fabulous way to make your Seder more accessible and interactive this year!

March 30,2012

Posted by Haggadot

Passover is almost here! If you are looking for some easy DIY projects to make this year’s Passover special and put your personal touch on the Seder, check out some of our favorites:

- Namecards - always a good idea to avoid chaos when arriving to the Seder table

- Personalized pillow covers - a great way to add to the reclining experience

- Make-your-own plagues - this one is for kids and those who are kids at heart

- Stylish centerpiece - a special way to set the tone for this “different” night

- Matzah napkin rings - THE cutest way to set the table for a Seder

March 29,2012

Posted by Jodi R.R. Smith Smith

Prelude to Passover

Tips for Children at Your Seder Table

Seder, loosely translated, means “order.” But in my house it never quite seemed that way. With 48 guests comprised of 3 generations of relatives and friends, our Seders were more like controlled chaos than an orderly affair. Yet we were always able to finish by midnight. This was because everyone, adults and children alike, knew what was expected of us at the Seder.

Children have always played an integral part of the Passover Seder. During the beginning of the Seder the Four Questions are chanted by the children at the table. The Seder continues with the story of the Four Sons, which is retold so that its meaning can be understood by all who have gathered. And, of course, the Seder meal can not conclude until after the children have found the Afikomen.

The key to a successful Seder with children is advanced preparation. Here are some tips to help your family prepare for Passover:

The Week Before the Seder:

- Have your children help you as you begin to prepare the house for Passover. Use this time together to discuss what Passover is and to share some of your memories of Passover from your childhood.

- Find an age-appropriate book about Passover to read to your children. Talk about your family’s traditions, whether they match or vary from the information in the book. This book can be brought to the Seder for the children to look at and read when they become fidgety.

- Begin reviewing the chanting of the Four Questions. The more often your children practice, the more comfortable they will be when reciting in front of the other Seder guests. Have a back-up plan just in case your child gets cold feet. Usually, help from an older sibling is enough to coax the questions out. So be sure to let older children know they might be pinch hitting.

- If the Seder is not at your house, check in advance with the hostess about logistics such as mealtime and seating arrangements. This information will help you plan ahead. If the meal will be later in the evening, you should make sure your child has a late lunch or snack. For some children, sitting next to a grandparent or an older cousin can be used as a reward for good behavior through the meal.

The Day of the Seder:

- Prepare your children for conversations with adults. Younger children should have short answers to questions such as how old they are, what grade they are in, and their favorite book. Older children should be prepared for conversational questions about what they are learning in school, what activities they are involved in and any upcoming plans. You can encourage children who are shy to become family detectives. They can ask relatives questions about family history. “How are the people in the room are related?” “How did the family come to America?” Or, they can ask questions that will elicit longer answers such as “What is your favorite Passover memory?”

- Remind your children of proper table manners. Review each utensil and its use. Make a game out of it. Have your children practice setting the table with the full setting of flatware. Ask your child what utensil they would choose for a particular food item or course. Doing so will familiarize your children with basic table manners so that they will be more comfortably during the Seder. In anticipation of some ceremonial foods your child might not want to eat, you may want to review what to do with food they do not like.

- Discuss with your children what behavior you expect at the Seder table and why it is important they behave in this manner. You may wish to cover when it is appropriate to be excused from the table, how to help clear the dishes, and topics of conversation.

- Let your children choose what special clothes they will wear to celebrate the holiday. With all of the rules guiding holiday behavior, doing so will allow your children to play a proactive part in the holiday.

- If you will be guests at a Seder, encourage your children to bring a gift. A picture they have created, or a box of candies (Kosher for Passover, of course), are a thoughtful way to thank your hosts.

While not every child will behave impeccably during the entire Seder, it is important to recall that even the Wicked Son plays an important role in the Seder. A bit of planning and preparation can go a long way in making your Seder as orderly and enjoyable as possible.

Jodi R. R. Smith of Mannersmith is a nationally known manners maven. To ask your etiquette emergency question please visit:

The Etiquette Book: A Complete Guide to Modern Manners now available!

March 28,2012

Posted by Haggadot

Make Your Own Seder Plate

Passover is less than two weeks away. (How did that happen—wasn't it just Purim)?!

If you're hosting a Seder at your house and want to try something new for a Seder plate you can easily put one together with dishes and platters found at stores you might not expect to find items for a Seder plate! Here's what I mean...

One Seder plate was put together with small bowls I found at Pier One Imports for only $1.50 each and they are sitting on a white platter from Crate and Barrel ($11.95). At $20.95 this is so affordable, you can probably put together several of these plates to use on a long table if you are having a lot of guests.

You can’t go wrong with classic white! Not only does white go with everything but the simple clean look gives a fresh feel to the Seder table.

Here's another look...

I used small green Capiz bowls which have a beautiful, shimmery finish like the inside of a sea shell and makes for an elegant Seder plate. These bowls are from Crate and Barrel and they were $2.95 each. They are sitting on a white square Capiz Shell place mat ($16.95). For a total of $34.65 it’s still an affordable Seder plate.

There are so many other dishes that could also work for a Seder plate—small plates shaped like leaves would be lovely, or maybe little square tapas plates. If you live near a Chinatown or an Oriental kitchen supply store, pretty small dishes used for soy and dipping sauces would be ideal.

Remember, any shape can be used…as the key to a kosher Seder plate is the placement of each dish.

More from the Design Megillah here: www.designmegillah.com

March 27,2012

Posted by Haggadot

March 26,2012

Posted by Haggadot

Haggadot.com is pleased to announce several new features for this Passover season. In addition to a brand new design and a growing library of content, other exciting new tools include:

- A checklist for putting together your Haggadah. Whether it's your first time or you're just a little rusty, our list explains each section that you need for a complete seder. See the checklist HERE

- Templates We have the traditional Haggadah text & translation, as well as a more liberal interpretation of the Haggadah. You can select a full template, print & go right to seder, or continue to personalize by adding and rearranging content. It's up to you!

- Videos You can now share audio & video content in your Haggadah. Check out some of our latest contributions HERE.

- An Instructional video & feedback tab. We know it can be challenging to learn a new online tool, so we're here to help. Check out our new instructional video, and feel free to send us comments on the feedback tab in the navigation bar.

- Group Haggadot Now, everyone in your family, shul, or other jewish organization can contribute to the same Haggadah, but you can continue to keep your personal profile & individual haggadah as well. NEXT is spearheading this effort with a collaborative Haggadah for Birthright alumni.

Now it's your turn to get creative! We're excited to host a contest to reward you for submitting your content. Share your clips through our social media "share" tool for a chance to win a $75 Amazon.com gift card!

How to Enter the Haggadot.com Share-a-thon Contest:

1) Create a clip on Haggadot.com with your original Haggadah text, artwork, music, or video.

2) Share a link to your clip through the "share" tool on the clip page. You can share it on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Google+, or any of the social tools listed in the "share" tool. The more you share, the better your chances of winning. Get your friends to help you out by sharing it too!

3) Keep sharing through Passover... The contributor with the most shares on the site wins!

You can enter as many times as you want, but remember to only post content that you've created yourself! And if you've already contributed a clip to the site, you can still share that as well.

The winner will be announced April 11, 2012!

Happy Sharing!

March 23,2012

Posted by Marc Michael Epstein

Medieval Haggadot, Contemporary Audiences

by Marc Michael Epstein

http://faculty.vassar.edu/maepstein/

The Haggadah has a long and distinguished history. And, in a wide spectrum of times and climes, it has been a book lavishly illustrated. Can one, after all conceive of a ritual moment more central to the Jewish experience as a whole than the Seder experience? Can one conceive of the Seder without the haggadah? And although they tend to be taken for granted can one conceive of the haggadah without the illustrations that accompany it?

Why the illustrations? Well, most discerning and aesthetically minded people tend to implicitly understand that the mandate to "expand upon the recounting of the Exodus" is not limited to text. A beautiful book with engaging, even mysterious illustrations can enhance the experience of putting oneself in the very shoes of those who hastily traversed the borders of the Land of Egypt on the night of the Exodus, fleeing the bondage of Egypt’s Pharaoh for the service of Sinai’s God.

Moreover, on the Seder night, one obligated to view oneself as if he or she had personally come out of Egypt. And Jews did so, graphically, in their illustrated haggadot, putting themselves into the picture, making the persons and places of the haggadah’s narrative their own.

The haggadah is a book for all seasons, for every individual. And in this sense, each haggadah from the most ancient to the most au courant and avant-garde is a “contemporary” haggadah. But lets be honest: There ARE some core values exemplified by contemporary haggadot that we tend to understand as characteristically postmodern and very exciting.

These include reflexivity and self-referentiality, meaning the ability not only to see ourselves in the story, but to see the story as applying to our particular individual circumstances. The story becomes our story, the tears of struggle become the tears of our struggle, the exhilaration of freedom becomes the exhilaration of our freedom, and the story becomes one about race, gender, oppression, homophobia, etc. etc.

As postmodern people, we also pride ourselves on the fact that our haggadot give us the critical distance to appraise and critique established religious, social and political norms.

The contemporary haggadah is a highly specialized affair, there are thousands out there, each aimed at a very particular constituency: There are vegetarian haggadot, secular haggadot, queer, feminist, gay and lesbian haggadot, hippy haggadot, historical haggadot, Holocaust Haggadot, hipster haggadot. This highly individuated approach, in which every haggadah is the haggadah of a particular constituency is a highly contemporary, postmodern approach.

This is somewhat ironic for me as a medievalist, of course, since all these contemporary haggadot are mass-produced, whereas each medieval manuscript haggadah was lovingly illuminated by hand for an individual person or family. The problem is that we cant tell very much about the intimate context of medieval haggadot, particularly those for which there is no provenance information (information about the origins of the manuscripts). What they may have meant to the individuals and families who commissioned them—the very information so crucial to us as contemporary viewers—seems to be irretrievably lost.

Even worse—it has long been the opinion of scholars of renown that medieval haggadot reflect the taste of the “Christian masters of the Jews,” and that many were likely illuminated by non-Jews, the whole project of determining what such a manuscript meant to the people who commissioned, viewed and treasured it seems doomed to failure. What, really, is there to say about such a work that will appeal to contemporary viewers, hungry as they are for haggadot that reflect particular, individual, intimate concerns? How much is there to appeal to them in what they might imagine to be highly conservative, stiff and stuffy, enigmatically impenetrable medieval book?

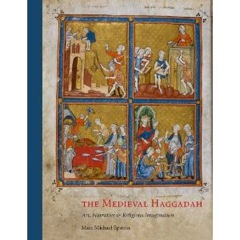

The fact is, there is a great deal to see and to learn. In my new book, The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination, (http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0300156669/) which has recently, I am pleased to report, sold out its first Yale University Press run after a stunning and humbling review as one of the “Best Books of 2011” in the London Times Literary Supplement, http://tinyurl.com/EpsteinTLS) I explore four magnificent and enigmatic illuminated haggadot with an eye, specifically, to the issues that most intrigue contemporary audiences.

I discuss the earliest known illuminated haggadah, the so-called Birds’ Head Haggadah, made in the Rhineland Valley around 1300, now in the collection of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. I attempt to get to the bottom of the mystery of the fact that in this book many of the faces on the human figures depicted throughout are replaced with those of birds. I discuss the ways in which Jews saw and projected themselves by means of these images.

Then, there are the Rylands Haggadah (now in Manchester) and its so-called Brother (in the British Library), both illuminated in Barcelona in the mid-14th century, and previously noted for their “nearly identical iconography.” Contrarian that I am, I examine their differences and learn a great deal from them about the nuances. It turns out that one of these “twins” is stridently political, socially critical, and religiously somewhat radical, while the other is much more conservative and quietistic. Clearly, although they were produced in nearly the same place and time, they emerge from entirely different socio-political contexts in spite of their apparent similarities.

But it is the most beautiful example, the Golden Haggadah, the one that appears on the cover of the book, that I enjoyed writing about most. Much of the scholarly attention focused upon this magnificent manuscript (made in Spain, probably Barcelona, around 1320, and now in the British Library’s collection) in fact accrues to it by virtue of its high style. In fact, the Golden Haggadah has often received the high compliment of being described as being devoid of all but the most superficial distinctive elements marking it as intended for a Jewish audience. “Funny —in other words—you don’t look Jewish.” Non-Jewish taste, most likely non-Jewish artists. Is there even a Jewish story here?

Part of my detective work in The Medieval Haggadah has been to demonstrate the inherent Jewishness of this work in spite of its manifestly non- or un-Jewish appearance. It may have been created by Jews or by non-Jews working for Jews. We don’t know. But one thing we do know is that this manuscript, which was very expensive, was created by whoever created it Jew or Gentile under the very direct guidance of Jews, some quite learned. The Golden Haggadah was the equivalent—both in price and in patron-generated input—of a postmodern architect-designed house! And the patrons were definitely Jews, so we are indisputably looking at a collaboration—a close one between—the designers and those who executed the design.

My book demonstrates how deeply the Golden Haggadah’s illustrations are informed by Jewish exegesis and rabbinic midrash, and how the “authorship” (the patrons and their rabbinic advisors) went beyond the mere literal illustration of scripture and midrash to add their own “special something” to the illustrations in the way of indigenous, contemporary political and social and even theological commentary. In this sense, the art becomes commentary, which, in many cases responds to or even subverts traditional literary commentaries.

In fact, I’m even able to show how even the very structure of the manuscript how the details of the illuminations are physically oriented in space is evidence of a concerted, detailed and Jewishly sophisticated plan.

I also discuss the ways in which the authorship of this manuscript adopts and adapts motifs from the wider culture, which certainly makes sense if you think about it, since the style of Jewish art tends to reflect the style of contemporary art in all times and places. But what happens when Jews and Christians use nearly identical images to tell very different stories? When Moses’ flight from Midian to Egypt is garbed in the same clothes—so to speak—as the image of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus’ so-called “Flight into Egypt”?

As Catalan Jews of the 1320s, the authorship of the Golden Haggadah were indistinguishable in many aspects of their external appearance and material culture from their Christian neighbors. In all their stylistic externals, they appeared not as distinctively Jewish, but as members of the wider society. But what they DO with the art is very different, and, as I argue in the case of this image, sometimes comes as a direct response or a challenge to the way the oh-so-similar image is employed in Christian culture.

Now that’s all very nice. But I’ll tell you a secret: I may study medieval haggadot, but I am a contemporary Jew. So I’m less interested in art or even in the haggadah than I am in people—Jews, specifically—and the individual, particular, and intimate concerns of those Jews. Who were the Jews who commissioned this manuscript? What were their lives like? Why was the manuscript made, and for whom?

The Golden Haggadah is an orphan manuscript. That is to say that we totally lack external information about who commissioned the manuscript and for what purpose, so no scholar has ventured to say more. But when I look at the manuscript, I see things and I cant keep silent.

In the book I go out on a limb beyond the normal bonds of documentary evidence into the realm of speculation (although the speculation is grounded in over three hundred contextualizing footnotes). But my research resembles nothing more than it does a detective story in the truest sense. It has all the proper elements—fortuitous discovery, a trail of clues, a speculation. True, it lacks real resolution, but give me a break— we’re dealing with a case that by any contemporary standard is “cold.” In another decade, the protagonists will have been gone 800 years.

Here’s the case: In looking over the structure of the manuscript, I began to notice something strange about the iconography. The Golden Haggadah is replete with no less than forty-six prominent depictions of women, and the biblical sequence culminates with a depiction of seven women in the illustration of the Song of Miriam and women and girls prominently involved in the scenes of Passover preparation. Scholars have placed no particular emphasis to the number of women or their prominence in these depictions. They have simply assumed that the women depicted in the Golden Haggadah simply represent “unremarkable actors necessarily demanded by the narratives depicted.”

Or were they?

My thesis in The Medieval Haggadah is that the Golden Haggadah was made for Catalan Jewish woman of around 1320, a woman who had experienced a particularly trying personal circumstance. My evidence? The internal iconography of the book, its pictorial preoccupations, a later ownership inscription, themes that appear again and again, even the representation of a particular woman. Can I “prove” this with certainty? Of course not. Does that bother me? Not at all. All I aim to achieve in this book is to come somewhat closer to what you and I—contemporary viewers that we are—crave to know about the intimate (in this case very intimate) context of the creation of this manuscript and the others I lovingly describe in the book.

Our haggadot are feminist, emotionally and spiritually questing, concerned with ethics, with loss, with restoration, with relevance. So when I discover forty-six women—hitherto unrecognized and unacknowledged in both their pain and their joy—calling out to me from the pages of a magnificent medieval book I cannot simply be silent about them in the face of a lack of conclusive external proof. Ought I go to my grave without ever sharing with you what I think they are trying to tell us?

You know, for years, the way the history of Jewish art was written was by scholars keeping their cards very close to their chests, controlling access to the manuscripts in libraries and museums, only showing the public what they wanted them to see. My new book bursts all this open —it provides complete facsimiles of all the manuscripts I discuss, in full color and in full size—so that the reader does not merely receive sound bites. My hope is that the boldness of my speculations and my openness with the material will urge other scholars and, even more importantly, perhaps— readers like you—to add their own voices to the discussion, and to be able to glimpse the lives of the people who made these wonderful and amazing books.